Advertisement

A Psychotherapist Explains How To Prioritize Needs Within A Family

As a psychotherapist and support circle facilitator, I often sit with folks as they contemplate the fine line between where others end and they begin. "How much of my needs should be met in any relationship, and how much of theirs?" they ask me.

Every relationship has three sets of needs: your needs, their needs, and the relationship's needs. However, there are times when these needs are opposing and therefore cannot all be fulfilled. So, what do we do when our children's needs abound (as they should!)? How do we decide which ones to meet and when to prioritize ourselves instead?

In many different parenting circles that I am a part of, I've heard the belief that children's needs must be met 100% of the time.

Some parents resent declining nights out with friends, canceling their massage appointment, or attending every single Little League game but choose to live with that resentment because they learned somewhere along the way that love means denying your needs and putting the needs of others before your own.

While there may be good intentions behind this effort, it can actually have the opposite effect when we over-index on meeting their needs. Over time, this teaches them to be self-deniers. This leaves many parents in a bind, myself included. As a new mom, I was afraid of replicating my own child dynamics and therefore felt anxiety about not "showing up enough," and yet noticed that showing up all the time left me feeling depleted and irritable.

Let's get into what the research says about how to find the sweet spot between your needs and your kids' needs and then five strategies for attuning to their and your needs, in a way that supports your bond with one another.

Attachment theory and the goal of raising securely attached children

Attachment theory, introduced by British psychologist John Bowlby in the 1950s, is the most widely cited and sound science we have available to help us understand how we relate to others.

Observations of mother/infant dynamics have been used as a basis to show us that the relationship we have with our parents or caregivers as babies impacts the types of relationships we have as adults.* This matters because the quality of our connections is a social determinant of personal health and happiness.

In children with secure attachment, we can see they possess the freedom to ask for what they want and they are easily soothed when they don't get it. This means that their caregivers were often emotionally—not just physically—present, attuned to, and accepting of their children's needs. Caregivers verbally and energetically communicated: "I see you, I hear you, and I am going to respond to you in a manner that is attentive, clear, and caring."

*A note from the author:

What is "often" when it comes to meeting our children's needs?

Responding to our children's needs doesn't mean meeting them all. All needs must be acknowledged, but that doesn't mean we drop everything that's happening to fill them.

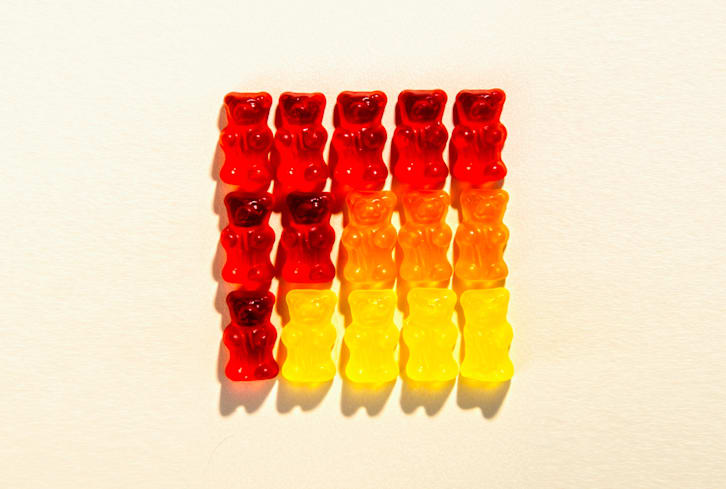

The recipe for secure attachment is:

- 33% of the time "getting it right": This is communicating that you hear the need and that you will meet the need. For example, when your little one asks you to read a book and you pause chopping vegetables to get down to their height and express that you'd love to read one book and you will take a break from cooking. They smile and it's clear the need is satiated.

- 33% of the time is having a rupture: You've missed the need, you didn't get what it was, you couldn't pay attention because you had too many other demands on your mind and body at the time, and there may be hurt or disappointment that your child feels as a result.

- 33% of the time is repairing: This is the most important step for developing secure attachment. It means that when we mess up, we acknowledge it and take responsibility for it by offering a wholehearted apology. We do not have to be perfect—in fact, teaching our kids how to fail and then grow from that failure is a very valuable life lesson—but we do have to be relationally responsible in order to build an honest and connected relationship with our kids.

Here are 5 steps for ensuring you navigate needs in a way that is right for your family

Here's how you can approach this dynamic:

Get clear on your beliefs, feelings, and experiences related to needs

Historically, I grew up as a self-denier. In my family system, it was better to not have needs than to acknowledge them because that would require me to feel the pain and deprivation associated with knowing they couldn't be met.

Humans deny their needs for many reasons—receiving what we want or need can orient us to the grief of what it was like to live without, neediness gets a bad wrap in our individualistic culture, and relying on others means we can become disappointed, to name a few.

If you had to deny your needs as a child, notice what your response to your kids' needs is. Do you respond immediately without checking in with yourself about your capacity? Do you want to run away from them but comply instead? Do you whisper to yourself, "MY GOD, I WAS SO EASY COMPARATIVELY?"

None of these reactions are bad' however, they say more about what you need than what your kid needs. Becoming mindful of these reactions allows you to have more choice in how you respond because they help you locate where you are at first. When our giving comes from an authentic place, this translates to the receiver.

Remember, if you deny all your needs, you are teaching your children to do the same, regardless of what you tell them about their rights to get their needs met.

Consider acknowledging ALL needs but only meeting SOME-MOST

If you are experiencing resentment in meeting your little one's needs, this is an indicator that you might be going past your limit. It's not only about complying with the need but rather the energy that we give with.

Some research suggests that 55% of communication is body language, 38% is the tone of voice, and 7% is the actual words spoken. If you are meeting a need with a proverbial eye roll or by dragging your feet, you're actually teaching your kid to be inauthentic. It could be helpful in these moments to get clear about why you are giving. And how do you feel about that reason?

Instead, consider honoring the need by validating how it deserves to be there, being clear about your inability to meet the need in that moment, and making a plan for the future.

This might sound something like "Of course you want me to stay home and play with you instead of me going out' we were having so much fun together. I am going to go out with my friend because I need time to play with my friends too. I want to hear all your feelings about this tomorrow, and I totally understand if you are sad or angry with me."

Give a "connected no"

Sometimes when we want to say no but feel guilty about it and therefore say yes, we act in ways that do more harm than giving a clean and simple "not right now" would.

For example, we might say yes to them (and therefore no to ourselves) so many times that we find ourselves feeling depleted and yelling and snapping at the end of the day (which is sometimes the only option for parents who live in a society that doesn't offer them the privilege of free or affordable child care support).

Or we'll sneak out when the babysitter arrives because we don't want to have to face our children's negative emotions about us leaving. Another common response is we'll say something like "after all I've done for you!" which indicates that we met their needs in order to not have to feel the lack of our own needs being met in our lives.

Giving from a site of depletion, hoping someone recognizes and gives back to you, can have a backlash effect over time, making our children feel responsible for meeting our needs because we aren't taking responsibility for meeting our own.

Track resentment

Resentment is an emotion that is actually a function of envy. You might not be mad because your kids have so many needs; you might actually be envious that they are so comfortable with owning their needs.

In these moments, it might be helpful to ask yourself: What do I need that I feel fear/judgment about asking for? Who can I sit with to help me work through the barriers to getting my own needs met?

Quality over quantity

It's not the number of yeses; it's how those yeses feel to you and your kid. Research shows that for young children, just five to 10 minutes daily of child-directed play can strengthen the bond between parent and child.

It might be helpful to refocus on the quality of the experiences versus the quantity of them (every waking moment!). What really matters to you and to your kid? How do you make space for ways of delighting in one another in the relationship?

The takeaway

Neediness is humanness. Separateness is at odds with our biology. There is nothing wrong with having needs or with our children having needs, but not all of them can and must be met to nurture well-adjusted and loving children. It's about how we interact with the needs that impact our relationships. If there is not enough of you (your needs, your feelings) in your relationship with your kids, then you are in essence taking yourself out of the connection and ultimately teaching them to do the same. Saying "I matter too," which isn't the same as "I matter more"—might actually strengthen, rather than harm, your bond.