Advertisement

What Is The Kinsey Scale? The Sexuality Spectrum's Uses & History

Charts and scales can help better explain many things in life, and sexuality is no different. One of the most popular scales used to understand sexuality is the Kinsey Scale, which was created to help describe a person's sexual orientation. Though not without its limitations, this scale can be a useful way for some people to make sense of their sexual orientation.

What is the Kinsey Scale?

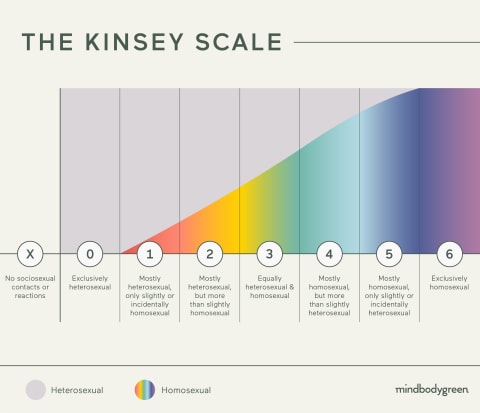

The Kinsey Scale is a visual representation of sexuality along a spectrum ranging from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. Originally called the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale, the Kinsey Scale was created by Drs. Alfred Kinsey, Wardell Pomeroy, and Clyde Martin and first introduced in their book Sexual Behavior in the Human Male in 1948.

"The scale was created as a way to 'measure' someone's sexual orientation beyond simply heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual, based on a spectrum-like scale where 'exclusively heterosexual' was on one end and 'exclusively homosexual' on the other," explains Anne Hodder-Shipp, multi-certified sex and relationships educator and founder of Everyone Deserves Sex Ed.

At the time, Kinsey's research found that most people fell somewhere between the two, Hodder-Shipp notes. This, and much of Kinsey's research, was considered subversive and groundbreaking for its time.

That said, today the scale is considered to have some limitations, both in terms of its ability to accurately represent the vast array of experiences of sexuality and because it excludes nonbinary folks. Not everyone will feel like they fit into one of these seven categories, and that's OK.

How to use the Kinsey Scale.

As mentioned, the Kinsey Scale is used to categorize a person's sexual attraction between exclusively heterosexual and exclusively homosexual. The scale runs from zero to six and includes an additional category labeled X, which attempts to represent asexuality.

Here's what each label represents:

- 0: Exclusively heterosexual behavior or attraction

- 1: Predominantly heterosexual and only incidentally homosexual behavior or attraction

- 2: Predominantly heterosexual but more than incidentally homosexual behavior or attraction

- 3: Equally heterosexual and homosexual behavior or attraction

- 4: Predominantly homosexual but more than incidentally heterosexual behavior or attraction

- 5: Predominantly homosexual and only incidentally heterosexual behavior or attraction

- 6: Exclusively homosexual behavior or attraction

- X: No socio-sexual contacts or reactions

(Note: Some versions of the scale use the term "slightly" instead of "incidentally," and "mostly" instead of "predominantly." So for example: "Mostly heterosexual and only slightly homosexual.")

How the Kinsey Scale was developed.

The Kinsey Scale was named after Alfred Kinsey, who is widely considered one of the 20th century's most significant sex researchers, according to sexologist Carol Queen, Ph.D. It's no stretch to say that without his work, today's sexual landscape would look very different and less diverse.

Kinsey, who was an entomologist, was hired at Indiana University to teach sex education, but there wasn't much to draw from. So, with the help of a team of grad students, he began doing his own research, much of which ultimately changed the world of sexual education and understanding.

The Kinsey Scale was developed in an attempt to show how sexual orientation (specifically, heterosexuality and homosexuality) existed on a continuum, or spectrum. A common misconception today, Queen adds, is that "Kinsey was trying to codify a binary way of looking at sex. This is ahistorical, though."

"People did think in binary, either/or terms in those days to a significant degree," she notes but adds, "Among other things, the Kinsey scale illustrates how significant bisexuality is since everything in the middle of the scale could be called bisexual."

Pros & cons of the scale.

We know much more today about sexual orientation, attraction, and human sexuality, and so while the Kinsey Scale was groundbreaking for its time, it also has its limitations. Like everything else, it has its pros and cons.

Pros:

It acknowledges the spectrum of sexuality.

The Kinsey Scale does an excellent job of debunking the "either/or" thinking surrounding sexuality. It was the first scientific scale to put forward the idea that sexuality is a continuum and isn't limited to being just heterosexual or homosexual. As Queen points out, the scale shows that sexual orientation can exist on a spectrum, and much of the spectrum thinking we do today—the ace spectrum, for instance—owes a lot to this conceptualization.

It highlights bisexuality.

The Kinsey Scale emphasizes the existence of bisexuality and the many ways a person can experience it, as expressed in its categories one through five. Kinsey's research at the time found 37% of the men interviewed had some kind of same-sex experience between adolescence and adulthood, and this number jumped to 50% for unmarried men by the age of 35. Among women, 13% had a same-sex experience. This data was groundbreaking for its time and made it clear that human sexuality was vast.

"It really helped make bisexuality visible, as well as helping bring homosexuality out of the closet. In my day (the '70s, when I came out), the gay movement very openly acknowledged its debt to Kinsey," Queen says.

Aids in understanding.

Queen says the Kinsey Scale can help a person (or a clinician working with people around sexuality issues) understand their own or their client's sexual experience, help them visualize their sexual orientation if they find it helpful to do so, and show that this experience is on a continuum and there may be room for them to explore different options than they have so far.

Cons:

Excludes nonbinary folks.

The Kinsey Scale "maintains the sex and gender binary," Hodder-Shipp points out. Describing people's behavior as exclusively some mix of "heterosexual" or "homosexual" depicts gender and sex in binary terms, making the Kinsey Scale less useful for those who are nonbinary. Some trans and intersex people may also find these categories limiting, not fully nuanced enough, or exclusionary.

The scale wasn't intentionally meant to exclude these groups of people, Queen notes; it is in many ways an artifact of its time, and language to describe gender diversity was simply in its infancy at the time the scale was developed.

Focuses on behavior rather than identity.

The Kinsey Scale focuses on behavior rather than identity. So rather than describing how much a person identifies as heterosexual or homosexual, it describes how heterosexual or homosexual their pattern of sexual behaviors has been. This distinction matters a lot to some people: For example, a lesbian who only came out later in life may largely have a history of having sex with men, but that doesn't mean she isn't a lesbian.

According to Queen, Kinsey didn't think it was appropriate to use orientation terms as anything but adjectives—he did not want us to use these words to define ourselves, but so far he has lost that battle with history, she says. "Still, when we think about why he felt so strongly, it might point to the fluidity of identity, or the way people can engage in all sorts of behavior that doesn't match their 'label,' and when we look at our history of behaviors and attractions, those are really useful insights."

Doesn't consider romantic attraction.

The Kinsey Scale focuses on sexual attraction without distinguishing between sexual and romantic orientations, sex and relationship coach Azaria Menezes points out. For some people, there's a difference between who we're sexually attracted to and who we're romantically attracted to, but this isn't accounted for on the scale.

Oversimplifies sexual orientation.

In general, many people today argue that the scale can feel like an oversimplification of how many people experience sexual attraction. "Though it did technically create new sexual orientation 'categories,' the scale still simplified sexual attraction in ways that can feel arbitrary and even confusing," Hodder-Shipp says.

"Like, what does it mean to be 'incidentally' homosexual or heterosexual? Where do I fall on the Kinsey Scale if I'm not really heterosexual but also definitely not homosexual? What if I feel lovey-dovey feelings toward pretty much any gender, but only sometimes feel sexually attracted to one gender?"

Can pressure people into categories they don't resonate with.

Some people don't desire to label their sexual orientation or attraction at all, Menezes points out. Not everyone feels comfortable being identified as a number on a scale, and with only seven points, the options are limited. And since there is so much new information when it comes to sexuality and seemingly infinite ways to experience sexual attraction, the Kinsey Scale may not quite "fit" anymore.

Other scales and variations.

Today, there are several other scales that try to present a visual representation of sexual orientation and identity. Two of the more popular and inclusive ones are the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid and the Storms Sexuality Axis.

- The Klein Sexual Orientation Grid is a direct riff on the Kinsey Scale. It was created by Fritz Klein in 1978 and has seven categories, including sexual behavior, sexual attraction, sexual fantasies, lifestyle preferences, and more. It works by having each respondent rate their preferences in each category across three different points in time—past, present, and ideal—which improves upon some of the limitations of the Kinsey Scale. The Klein scale also does a better job of including the ace spectrum, as well as other gender identity scales of today, says Queen.

- The Storms Sexuality Axis was developed by Michael D. Storms and plots eroticism on an X and Y axis, with heterosexuality on the Y-axis and homosexuality on the X-axis. While it expands on Kinsey's ideas, it also allows for more inclusivity and considers infinitely more categories of bisexuality as well as asexuality.

The bottom line.

The Kinsey Scale was incredible and ahead of its time, but in many ways, it may not quite fit how we talk about sexuality and sexual identity today. It's not a one-fits-all situation, and you absolutely don't have to fit or identify within the Kinsey Scale.

If you do find yourself identifying with the parameters set on the scale, Menezes suggests "taking what you love and leaving the rest."