Advertisement

A Guide To The Most Common Types Of Probiotics & What They Do

When you hear the word "probiotics" you probably think of gut health. And for good reason. In addition to filling our fridges with probiotic foods like yogurt and kombucha, probiotics have quickly become one of the most popular supplements in the United States.

In fact, the 2012 National Health Interview Survey showed that about 4 million people take them to support everything from healthy digestion to bloat and immune function.* (And that number has likely spiked in the last month thanks to issues like regularity struggles and excess bean bloat.)

Despite their popularity, it's important to note that there's no one-size-fits-all approach to probiotics. There are many different types of probiotics—called strains—and each one has its own special function. Every person also has a unique gut microbiome—or balance of beneficial bacteria in the gut—so the best probiotic for you may be different from the ideal choice for someone else.

To get the most benefits of probiotics, you need to find the strain(s) targeted to your specific symptoms.

What are probiotics?

Your body is home to trillions of bacteria1. While that bacteria takes up residence everywhere in your body, the majority of it lives in your gut. This bacteria, your microbiome, plays a critical role in your health.

Probiotic supplements are living microorganisms (usually bacteria or yeast) that help maintain balance in your gut microbiome.*

Aside from supporting your gut health and combating uncomfortable digestive issues, like bloating and regularity struggles, probiotics have also been linked to a healthier immune system.*

Because probiotics are so popular, manufacturers have made the supplements readily available in all forms. You can find them as pills, capsules, and powders.

Probiotics are even frequently added to other supplements, like greens powders, to boost their nutritional value.

Summary

How probiotic strains get their name

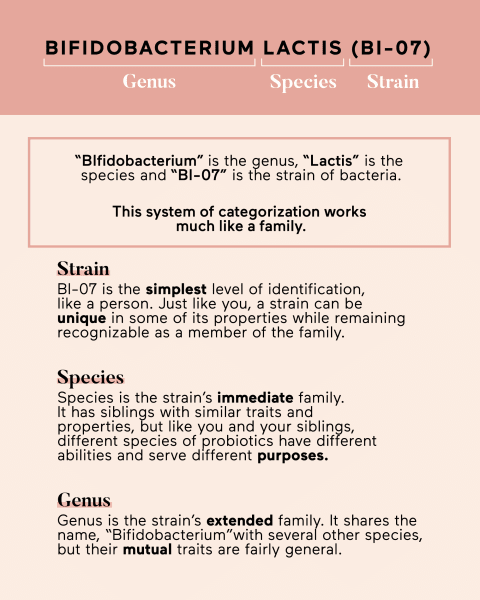

All probiotics have three different qualifiers: genus, species, and strain (in that order).

For example, when looking at Bifidobacterium lactis BI-07, Bifidobacterium is the genus, lactis is the species, and BI-07 is the strain. But what does that all mean? Below, we've broken it down.

- Genus: Genus is the broadest identifier. It encompasses several different types of bacteria in the same general category but with lots of different characteristics and health benefits.

- Species: The term species gets a little more specific. All of the bacterial strains within a species have similar characteristics but with some subtle differences between them.

- Strain: A specific strain is one type of bacteria. All of the bacteria identified within a strain carry out the same function within your body.

Bifidobacteria vs. Lactobacillus: What's the difference?

One of the main differences between Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria is the beneficial byproducts they produce2.

Lactobacillus ferment refined sugars and create lactic acid, while bifidobacteria mainly produce short-chain fatty acids, or SCFAs, although they create lactic acid too.

Another difference is where they live and colonize (or grow). Lactobacillus naturally lives in the small intestine, while Bifidobacterium takes up residence in the large intestine (or colon).

That also means that when you take a probiotic supplement, the Lactobacillus strains travel to—and grow in—your small intestine, while the Bifidobacterium strains have a longer journey to get to your large intestine.

These different locations in your gut translate to different health benefits.

Bifidobacteria

Bifidobacteria, which are gram-positive anaerobic bacteria, play a huge role in promoting normal inflammatory processes in the gut3 and helping you digest carbohydrates.

In most adults, Bifidobacteria makes up 3 to 6%4 of the total gut microbiome, making it one of the most abundant genera5.

There are about 48 different Bifidobacterium species6, and each affects your health in different ways. In general, some of the health benefits associated with Bifidobacteria include:*

- A healthy immune function5

- A better physiological response to stressors7

- Healthy digestion

- Mood regulation8

Lactobacillus

Research shows that Lactobacillus can support gut barrier function10 by killing off potentially harmful bacteria.*

There are about 170 different species of Lactobacillus, and the general health benefits include:*

- Supporting the digestion of lactose11 or milk sugar

- Healthy digestion and bowel regularity12

- Positively affecting total cholesterol levels13

- Supporting immune function13

- Promoting better sleep7

Summary

Common species and strains in probiotics

Of course, there are many species within the Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus genera and many different strains within those species.

Researchers have yet to identify every single probiotic strain out there (and it's likely they never will), but that number currently is almost at 8,00014.

Even though some bacterial strains may always remain a mystery, there are some have a long history of good research and clinical use. These include:

Bifidobacterium lactis HN019: shown to support regularity15.*

Bifidobacterium animalis DN-173 010 (nicknamed Bifidus regularis): may shorten colon transit time16, which can promote regularity and aid healthy bowel movements.*

Bifidobacterium longum BB536: promotes bacterial balance17 and homeostasis in the gut, which supports the immune system and alleviates digestive issues.*

Bifidobacterium lactis UABla-12 and Lactobacillus acidophilus DDS-1: can support abdominal comfort18 and reduce the severity of other issues like bloating.*

Lactobacillus casei Shirota and Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010: might increase stool frequency19 and improve stool consistency, which can help promote bowel regularity.*

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus fermentum RC-14: can help restore normal vaginal flora20.*

Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB-1: positively affects GABA21, a neurotransmitter in the brain, and may support stress resilience.*

Lactobacillus casei BF1, BF2, and BF3: can inhibit the growth of Helicobacter pylori and Staphylococcus aureus22, two pathogenic bacteria well known for causing immune struggles and resulting health problems.*

Lactobacillus reuteri NCIMB 11951, Lactobacillus reuteri NCIMB 701089, and Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 314: can promote healthy cholesterol levels23 and support heart health.*

Lactobacillus plantarum DSM 9843: can improve gas and flatulence24.*

Summary

Choosing a probiotic supplement

According to Vincent M. Pedre, M.D., a board-certified internist, the bacterial strains that are actually in many commercially produced supplements don't match the claims on the bottle. That's why it's important to get your supplements from a reputable, high-quality manufacturer.

He recommends choosing a probiotic that's targeted to what you're trying to treat, contains multiple strains, and 5 to 100 billion colony-forming units (CFUs).

It's also a good idea to make sure your probiotic is tested by a third-party lab to ensure that it contains what it says and that the bacterial strains are alive and doing their jobs.

Note that while many probiotic supplements are refrigerated to help with this, high-quality supplements can also be made shelf-stable and don't require refrigeration.

For more specific recommendations, check out one of our probiotics roundups:

Summary

The takeaway

While probiotic supplements have a long list of health benefits, from gut support to immune function, there are many different strains of bacteria in probiotics, each with its own special functions.*

Understanding the different strains is key to finding a targeted supplement and reaping those benefits.

24 Sources

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4991899/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4818210/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4879732/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4908950/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5722804/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4155821/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00730/full

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00164/full

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5808898/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5964481/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4875742/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5670282/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5601789/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-019-0559-3

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5266733/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC6219592/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756464619300684

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32019158/

- https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/100/4/1075/4576460?login=false

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/pmc/articles/PMC5819037/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0271531720304899?via%3Dihub

- https://www.nature.com/articles/nrmicro.2016.142

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4176637/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3419998/