Advertisement

How My Grandfather Lived Into His Late 90s Using These Ayurvedic Principles

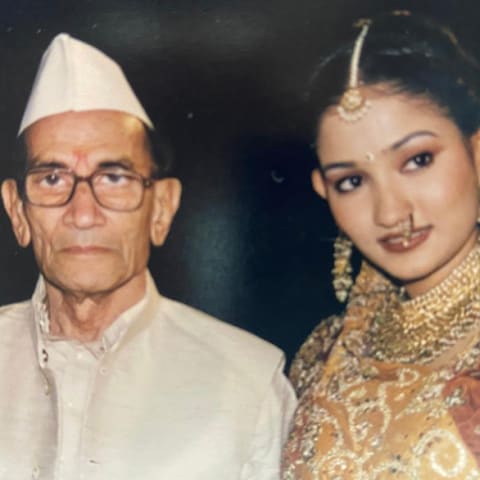

In 2007, my grandfather lay on his deathbed with over 35 members of his family lovingly gathered around him to say their goodbyes. He had peace in his heart and a sense of fulfillment on his face. He had almost all his dark hair, a heart that functioned like an 18-year-old boy's, and no chronic or acute conditions. He had amazed the doctors at every visit.

We lived in Mumbai—a city where human bodies tend to deteriorate rapidly. The Air Quality Index usually hovers around 150, 50 points above what the WHO considers acceptable for most people, and the tropical sun shines hot and bright. But my grandfather, an Ayurvedic healer, had used a combination of Ayurvedic and Yogic principles to defy aging and live his life to its fullest potential.

Bapuji would volunteer at various dilapidated municipal hospitals with low hygiene standards to distribute free medicine and personally greet lonely patients on every bed—he did this up until his 90s. Most of these buildings had no elevators, and often, he would walk up seven stories, no cane, no support. The family often displayed their concern for infections, but he remained undaunted. He had trust in his body's ability to protect itself, and in the 30 years of these visits, he never once caught something.

Today, 14 years after his passing, his remarkable Ayurvedic life still inspires me daily, and I carry his legacy to the West. Below are 10 of the core tools, practices, and principles that kept him thriving.

Early mornings

Bapuji's 4:30 a.m. alarm often interrupted my REM sleep, as he slept on a floor mattress in a room with my four sisters and me. ("Sleeping close to the ground keeps me grounded," he'd joke.) He woke up at Brahma Mahurat, the hours between 4:30 and 5:20, to take advantage of theta brain wave patterns, tap into the subconscious mind, self-reflect, and alter brain chemistry in the morning. He believed that a man who wakes up early sees more of the world and remains inspired to make good of his life.

Abhyanga (massage)

Abhyanga, massaging the body and head with oil before exercise, was a practice he never missed. In Sanskrit, "oil" is called sneha, a word that also means "love." This self-loving practice is not only grounding, but it also utilizes the skin as the channel of consumption to nourish deeper tissues, regulate the nervous system, enhance vitamin D synthesis, and keep the skin radiant. In addition, Bapuji used specially formulated oil on his head to keep his hair all black and his brain cool.

Neti pot

As the population grew and new homes were built that supported mold growth, much of Mumbai developed allergies and congestion. But Bapuji used a neti pot daily to keep his nasal passages free of allergens and microorganisms. After all, he knew that how and what you breathe is as important as how and what you eat.

Gold-treated water

Boiling a 24-carat gold chain in water used for drinking is a powerful and fascinating Ayurvedic practice that Bapuji used for healthy aging and immune modulation. Ayurveda utilizes gold to regulate the body's environment, fight diseases, enhance memory, and protect life. It also purifies and changes the composition of water to make it lighter. For Bapuji, this alone was a life-changing practice.

Diet

Contrary to what you might think, Bapuji never ate for his dosha, despite being an Ayurvedic healer. He believed that the doshic balance in the body is constantly shifting, and it was purposeless and tedious for anyone to eat for any one dosha. Instead, he ate an Ayurvedically balanced diet, which he would mildly tweak if a symptom was present. He never gave up any particular food item but consumed everything in moderation, chewing each bite slowly and mindfully. He would often say that man runs all day to get food on the table; the least he should do is slow down to enjoy it.

Breakfast was always warm to offset the cool, dewy environment morning brings. All meals were vegetarian, fresh, warm, well-spiced, and cooked in ghee. Mung lentils were an essential part of the dinner for the entire family, and he made sure to educate all of us on the importance of shifting foods as the seasons shifted.

Family

My grandmother died when Bapuji was 50, so he remained single for 40-plus years. But he lived in a joint family system with his three sons, three daughters-in-law, and seven grandchildren, including me. Culturally, his patriarchal status could allow him to dictate all family matters. Still, he was quick to hand over the baton to his sons and use the opportunity to disentangle himself from worldly affairs. Moreover, he compassionately witnessed each one's journey and led by example. As a result, not only was he dearly loved and respected, but he remained stress-free in a parasympathetic mode so his body could continually repair and heal.

Fasting

Being from the Jain tradition, Bapuji followed intermittent fasting as a lifelong practice. Jains often stop eating before sunset and do not eat until sunrise. It allows the body to take a break at a time when the digestive fire burns the lowest.

Bapuji also did a full 36-hour fast every two weeks. He fasted not only to give the digestive fire a chance to flush out toxins and undigested waste but also to disengage from the tongue and other senses for a deeper spiritual connection. He continued to fast until he was well into his 90s.

Yoga and breathwork

Bapuji adopted a yoga and pranayama practice when he was a young boy at boarding school, and it became an essential part of his daily routine. Exercise was only a side benefit of his yoga practice. He maintained that its true purpose was to regulate organ secretions, soothe the nervous system, stimulate the endocrine glands, and change the body's electromagnetic field. As a result, all 14 members of my family were inspired to adopt a strong practice too.

Self-sufficiency

Despite plenty of staff and a large family eager to help, Bapuji chose to do all his tasks except for cooking independently. This included hand-washing his garments and mopping the floor of his room. He believed that a person's self-worth depends on how self-sufficient they can be. Once someone becomes overly dependent on others, they lose confidence, and aging speeds up, he'd say.

Yathashakti

One would imagine that a lifestyle as disciplined as Bapuji's would require some rigidity. However, the opposite was true. He believed in the principle of Yathashakti, which means "according to one's ability." He maintained that a balanced life is not a rigid prescription but should happen in a state of flow. "If it disturbs your flow, drop the practice," he'd say.

He worked hard to expand this state to other areas of his life too. This meant that if for any reason his routine caused inconvenience to another, he would be quick to let it go. The purpose of his life was to move away from charge and toward flow.

The takeaway.

My heart feels full as I recall my grandfather's simple yet powerful life. His secret sauce does not lie in complicated practices but rather in simplicity and practical wisdom. He taught me that for real change, one must inspire but never impose and that health is not the fear of disease but rather the freedom that comes from being well.